Individual Vs Family Focus in Native American Healthcare

Introduction

American Indians and Alaska Natives face persistent disparities in health and health care, including high uninsured rates, meaning barriers to obtaining needed care, and poor health status. While the Usa has a unique responsibility to provide health intendance for American Indians and Alaska Natives, which is primarily carried out through the Indian Health Service (IHS), chronic underfunding and other barriers continue to limit access to care for the population. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) offers of import opportunities to increment health coverage and treat American Indians and Alaska Natives, helping to reduce the longstanding disparities they confront. This cursory provides an overview of health coverage and intendance for American Indians and Alaska Natives today and the potential implications of the ACA coverage expansions.

Central Characterisitcs of American Indians and Alaska Natives

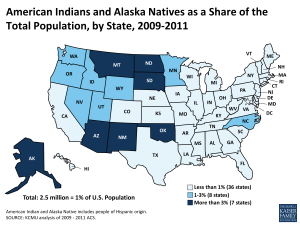

Effigy i: American Indians and Alaska Natives as a Share of the Total Population, by State, 2009-2011

A total of 5.1 one thousand thousand individuals self-identify as American Indian or Alaska Native lonely or in combination with some other race, representing ii% of the full U.Southward. population. This includes some ii.five million individuals who identify solely as American Indian or Alaska Native, making upward about ane% of the total U.S. population. American Indians and Alaska Natives live throughout the country, but are concentrated in certain geographic areas. In 7 states, American Indians and Alaska Natives incorporate over 3% of the total population (Alaska, Arizona, Montana, New United mexican states, North Dakota, Oklahoma, and Southward Dakota) (Figure 1).Moreover, over half (54%) of the total American Indian and Alaska Native population resides in only seven states (Effigy two). American Indian reservations, country trusts, or tribal statistical areasane are located in all just 13 states and the District of Columbia with some tribal boundaries extending across more than ane country.2 While many American Indians and Alaska Natives live in rural areas, only 22% currently alive on reservations or land trusts and, as of 2010, some 60% lived in metropolitan areas.three The share of American Indians and Alaska Natives living away from reservations has grown steadily over time and this demographic shift is expected to continue.4

Figure 2: Distribution of American Indians and Alaska Natives Beyond States, 2009-2011

Some American Indians and Alaska Natives vest to a federally-recognized tribe, some belong to a state-recognized tribe, and others self-identify every bit American Indian and Alaska Native, simply are not enrolled in a tribe. There currently are 566 federally-recognized sovereign tribes5 and more than 100 state-recognized tribeshalf-dozen in the The states. Each tribe has its own eligibility requirements and unique customs and beliefs and more than 200 tribal languages are withal spoken. Federally-recognized tribes share a government-to-government relationship with the federal authorities based around the "Federal Trust Responsibility." Treaties and laws accept established the federal government'due south responsibility to provide members of federally-recognized tribes certain rights, protections, and services, including health care. As such, members of and descendants of members of federally-recognized tribes take broader access to certain federal benefits.

Compared to the U.Due south. population every bit a whole, the American Indian and Alaska Native population is younger and has lower education levels. I in three American Indians and Alaska Natives is nether age nineteen (31%) compared to 26% of the U.Southward. population, while but 7% of American Indians and Alaska Natives are over the historic period of 65 compared to 13% of the U.South. population. With regard to educational attainment, four in ten (40%) American Indian and Alaska Native adults take completed at least some college or college, compared to over half of the overall adult population (54%).7

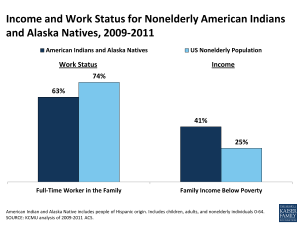

Figure 3: Income and Work Status for Nonelderly American Indians and Alaska Natives, 2009-2011

While the majority of nonelderly American Indians and Alaska Natives are in working families, they are less likely than the overall nonelderly population to be in the workforce and accept significantly higher poverty rates than the total nonelderly population (Figure 3). Some 63% of nonelderly American Indians and Alaska Natives are in a family with at least one full-fourth dimension worker, compared to 74% of the U.Southward. nonelderly population. Reflecting this employment pattern, the poverty charge per unit for American Indians and Alaska Natives (41%) is more than one and half times the overall rate for the nonelderly population (25%).viii However, despite this overall high rate of poverty, there is variation in economic status among American Indians and Alaska Natives. For instance, there has been successful economical evolution amid tribes, not only through gains stemming from casinos and natural resources, but also among tribes with a strong focus on American Indian and Alaska Native entrepreneurship and business concern evolution.9

Figure iv: Wellness Status and Rates of Selected Chronic Diseases for American Indian and Alaska Native Nonelderly Adults, 2011

American Indians and Alaska Natives accept high rates of physical and mental wellness problems. Among nonelderly adults, American Indians and Alaska Natives are significantly more than likely than the overall population to report being in fair or poor health, beingness overweight or obese, having diabetes or cardiovascular disease, and experiencing frequent mental distress (Figure 4).x American Indian and Alaska Native children and adolescents are too at higher risk for health problems than their peers. Nearly four in ten American Indian and Alaska Native children are overweight or obese, and studies have found the overweight and obesity rates among American Indian and Alaska Native children to be college than whatever other group.xi In addition, the suicide rate for American Indian and Alaska Native adolescents and young adults is two and half times higher than the national average, and suicide is the second leading cause of decease amid American Indian and Alaska Native adolescents and young adults, compared to the eleventh leading cause of death nationally., 12

Wellness Coverage and Intendance

As noted, the U.S. regime has a unique responsibility to provide health care services for American Indians and Alaska Natives that is primarily the responsibility of the IHS. Notwithstanding, the IHS is subject to funding restrictions that limit the provision of care to the population. Given the limitations of IHS, health insurance coverage remains important for providing access to health care for American Indians and Alaska Natives, with Medicaid playing a particularly of import role. Still, overall, American Indians and Alaska Natives remain significantly more likely to exist uninsured than well-nigh other groups.

Role of the Indian Wellness Service

The IHS is responsible for providing health care to American Indians and Alaska Natives. The IHS is the main federal health care provider for Indian people, and its goal is to raise their health status to the highest possible level.xiii In addition to medical care, the IHS provides a wide range of other services, including sanitation and public health functions. The IHS provides health care and disease prevention services to approximately 2.2 one thousand thousand American Indians and Alaska Natives through a network of hospitals, clinics, and wellness stations.14 Health services are provided through facilities that are managed directly past IHS, past tribes or tribal organizations nether contract or meaty with the IHS, and urban Indian health programs. Equally of 2013, at that place are a full of 612 IHS- and tribally-operated facilities located mostly on or well-nigh reservations, some lxxx% of which are operated by tribes.15 In addition, there are 33 urban Indian programs operating in 40 sites located in cities throughout the U.S.sixteen If facilities are unable to provide needed care, the IHS and tribes may contract for health services from private providers through the Contract Health Services (CHS) program. However, urban Indian health organizations do not participate in the CHS program and do not receive CHS funding for additional health services beyond the scope of what they tin provide. Overall, the services provided through the IHS consist largely of primary intendance, but include some ancillary and specialty services. American Indians and Alaska Natives receiving services through IHS providers are not charged or billed for the cost of their services.

Directly services provided through IHS- and tribally-operated facilities mostly are limited to members or descendants of members of federally-recognized tribes, including Alaska Natives and California Indians, who live on or well-nigh federal reservations. Moreover, due to limited funding, services through CHS are largely reserved for American Indians and Alaska Natives who reside on reservations or within specific geographic areas nearby and are often rationed based on medical demand, such as emergency care for life-threatening illnesses and injuries. Urban Indian health programs serve a wider group of American Indians and Alaska Natives, including those who are not able to access IHS- or tribally-operated facilities because they exercise non meet eligibility criteria or because they reside outside their service areas. However, funding to urban Indian wellness programs is very express and the share of IHS funding going toward urban programs over time has not reflected the overall demographic shift of American Indians and Alaska Natives away from reservations.17 Individuals who rely solely on IHS for care without any form of health insurance coverage are classified by the U.S. Demography equally uninsured. Both insured and uninsured American Indians and Alaska Natives may seek care at IHS and tribal facilities.

Effigy 5: Allocation of Indian Wellness Service Program Funding, in Billions, FY2013

Equally a discretionary plan, IHS funding is limited and must exist appropriated by Congress each fiscal yr. The appropriated funds are distributed to IHS facilities across the country and serve as their annual budget. If service demands exceed available funds, services are prioritized or rationed. In FY2013, a total of $4.iii billion was appropriated for IHS services, with $three.1 billion going to health care services and the remaining funds supporting preventive wellness and other services (Figure 5).18 Over half (57%) or $1.8 million of the $3.1 million going to direct health services was appropriated to tribally-operated facilities, with the remaining $1.3 million going toward those directly operated past IHS. Only 1% of total plan funding was directed toward urban Indian health.

In addition to direct appropriations, revenues from third-party payers are a pregnant office of IHS funding. Given that appropriations have been insufficient to enable many Indian hospitals and clinics to run across the needs of the populations they serve, they often rely on revenues from 3rd political party payers, including Medicare, Medicaid, the Veterans Administration, and private insurance, to help reduce shortfalls between capacity and need. In fact, IHS regulations require that the facilities the IHS operates, as well as those run by tribes or by urban Indian health programs, identify and recover third party resources.nineteen A total of $973 million volition be collected from third political party payers in FY2013. Past far the largest third-party payer is Medicaid, which accounts for $683 million or lxx% of full third political party revenues, and 13% of total IHS program funding for FY2013.20

IHS has historically been underfunded to run across the wellness care needs of American Indians and Alaska Natives. Although the IHS discretionary budget has increased over time, funds are not equally distributed across IHS facilities and remain insufficient to come across health care needs.21 Equally such, access to services through IHS varies significantly across locations, and American Indians and Alaska Natives who rely solely on IHS for care often lack access to needed care, including preventive intendance and early treatment of chronic diseases.22Moreover, access to services through CHS is significantly limited with available funding oftentimes simply able to support "medical priority ane cases, or those that threaten life or limb."23

The Office of Medicaid

While the roughly 700,000 American Indian and Alaska Native Medicaid beneficiaries make up a small portion of total Medicaid beneficiaries, Medicaid is an of import source of health insurance coverage for the population.24 Medicaid helps to fill the large gaps in private coverage for American Indians and Alaska Natives and provides a cardinal source of financing for IHS providers. Moreover, the Medicaid program includes a number special financing rules and consumer protections that apply to American Indians and Alaska Natives.

Figure half dozen: Health Insurance Coverage for Nonelderly American Indian and Alaska Natives Compared to U.S. by Age, 2009-2011

Medicaid fills gaps in private coverage for nonelderly American Indians and Alaska Natives, simply nearly one in iii (30%) remains uninsured (Effigy 6). American Indians and Alaska Natives accept limited admission to employer-sponsored coverage considering they have a lower employment rate and those working tend to exist employed in low-wage jobs and industries that typically exercise not offer health coverage. Less than four in x (36%) nonelderly American Indians and Alaska Natives have individual health insurance coverage, compared to over six in x nonelderly in the U.S. (62%). Medicaid helps fill this gap, covering one in three (33%) nonelderly American Indians and Alaska Natives. However, Medicaid does not fully offset the divergence, leaving nonelderly American Indians and Alaska Natives significantly more than likely to exist uninsured than the national average (30% vs. 17%). Medicaid plays a more than expansive part for American Indian and Alaska Native children than adults, roofing more than half of American Indian and Alaska Native children (54%) versus 23% of nonelderly adults. As such, the uninsured rate for nonelderly American Indian and Alaska Native adults is nearly twice that for children (37% vs. eighteen%).25

Just as with other eligible individuals, American Indians and Alaska Natives who come across land eligibility standards are entitled to Medicaid coverage in the state in which they reside. Medicaid eligibility is determined by states inside federal guidelines. As a outcome, eligibility criteria vary considerably from state to country. Overall, states take significantly expanded eligibility for children, while eligibility levels for parents remain very low in most states. Moreover, until the enactment of the ACA, other non-disabled adults, oft referred to equally "childless adults," were excluded from the program, regardless of how depression their income was. An American Indian or Alaska Native who meets the Medicaid eligibility criteria of the state in which he or she resides is entitled to Medicaid coverage. This is true whether or not the individual is a member of a federally-recognized tribe, whether or non the private lives on or off a reservation, and whether or non the individual receives services (or is eligible to receive services) at an IHS- or tribally-operated hospital or clinic. American Indians and Alaska Natives with Medicaid can access care through all providers who accept Medicaid for all benefits covered by the land Medicaid plan. Equally such, they take access to a broader array of services and providers than those who rely solely on IHS services for intendance.

Many American Indians and Alaska Natives are eligible for Medicaid but remain uninsured due to an array of enrollment barriers. Common barriers to Medicaid enrollment include lack of noesis about the program, difficulty completing the enrollment process, linguistic communication and literacy barriers, and geographic and transportation barriers. In improver, there are some barriers specific to the American Indian and Alaska Native population, including mistrust of federal and state governments due to historical conflicts, sure cultural beliefs, a preference for relying on IHS services for care, and the conventionalities that the federal government has the responsibility to provide and fund all needed care through the IHS.26

Medicaid has special eligibility rules and provides specific consumer protections to American Indians and Alaska Natives. These include exemptions of certain types of property in determining whether American Indians and Alaska Natives see income and resources standards for Medicaid eligibility as well every bit enhanced consumer protections with respect to price sharing and managed intendance (See Text Box 1, next page). Consequent with American Indian and Alaska Native eligibility for IHS services, these provisions utilise to American Indians and Alaska Natives who are members or descendants of members of federally-recognized tribes, including Alaska Natives, California Indians, and the broader group of American Indians and Alaska Natives eligible for urban Indian programs.27

As is the case for other Medicaid providers, federal Medicaid funding is bachelor for covered services provided through IHS facilities, tribally-operated facilities, and urban Indian health programs. Similarly, if an American Indian or Alaska Native enrolled in Medicaid is referred for CHS, Medicaid pays for the covered services. In contrast to IHS funds, which are limited at a stock-still amount appropriated per year, Medicaid funds are not field of study to almanac appropriation limits. In improver, since Medicaid claims are candy throughout the yr, IHS facilities receive Medicaid payments on an ongoing basis. Every bit such, Medicaid revenues can help IHS facilities cover needed operational costs, including provider payments and infrastructure developments, supporting their ability to see demands for intendance and maintain intendance capacity.

The federal government covers 100% of the cost of covered Medicaid services provided to American Indian and Alaska Native beneficiaries through IHS- or tribally-operated facilities. Medicaid is a federal-state matching program—the federal government matches the costs states incur in paying for covered services provided to eligible individuals. The charge per unit at which the federal government matches land Medicaid costs varies across states from l% to 74%, depending on a state's per capita income.28 Nonetheless, the federal government matches 100% of a state'southward costs for services provided to American Indian and Alaska Native beneficiaries through an IHS- or tribally-operated facility.29 This 100% matching rate reflects a policy judgment that states should non have to contribute state general funds to the cost of intendance provided past a federal facility, whether operated past the IHS or on its behalf by a tribe. In contrast, a state's regular federal matching charge per unit applies to the cost of services provided to American Indian and Alaska Native beneficiaries through an urban Indian health program or non-Indian health provider. In addition, there is a special financing dominion that applies to tribal and urban Indian providers, which are designated under federal law as federally qualified health centers (FQHCs). Specifically, these providers may elect to either be paid the IHS charge per unit established each year with the Office of Management and Budget or to use the same payment methodology as other FQHCs.thirty

Text Box 1: Medicaid Protections for American Indians and Alaska Natives

States are prohibited from counting certain types of property as resource in determining Medicaid eligibility for American Indians and Alaska Natives. These include lands held in trust past the federal regime and items that accept unique religious, spiritual, traditional or cultural significance. Similarly, states are prohibited from recovering sure income or property from the estates of deceased Indian beneficiaries to reimburse the Medicaid program for the costs of long-term care services received after age 55.( Section 1902(ff) and Department 1917(b)(3) of the Social Security Act ; State Medicaid Manager Letter, ARRA Protections for Indians in Medicaid and CHIP (SMDL #10-001) (January 22, 2010).)

American Indians and Alaska Natives are exempt from Medicaid premium and cost-sharing requirements. Land Medicaid programs have the flexibility to impose copayments and other types of price-sharing requirements on certain services for certain beneficiaries. However, American Indian and Alaska Native beneficiaries are exempt from all Medicaid toll-sharing if they have ever received a service straight from an IHS or tribally-operated facility, from an urban Indian health program, or through a referral nether CHS. Similarly, states may not accuse American Indian and Alaska Native beneficiaries premiums for enrolling in Medicaid. This aligns Medicaid policy with IHS policy, under which American Indians and Alaska Natives receiving services at IHS facilities are not expected to contribute toward the toll of the service. ( Sections 1916(j), 1916A(b)(three)(A)(vii) , and 1916A(b)(3)(B)(x) of the Social Security Deed; Country Medicaid Director Letter, ARRA Protections for Indians in Medicaid and CHIP (SMDL #10-001) (Jan 22,2010).)

States do not have optional dominance to require American Indians and Alaska Natives to enroll in Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs), unless the MCO is operated past the IHS, a tribe, or an urban Indian health program State Medicaid programs have broad discretion to determine whether beneficiaries will receive covered services on a fee-for-service basis or through risk-based MCOs. In general, states can crave most groups of beneficiaries in urban areas to enroll in risk-based managed care and then long equally the beneficiary has a choice betwixt at least two MCOs that run across federal standards; in rural areas, states may limit beneficiaries to one MCO. However, under federal rules, states do non accept the choice to require American Indians and Alaska Natives to enroll in Medicaid MCOs unless the MCO is operated by the IHS, a tribe, or an urban Indian health program. However, the Secretary is authorized to waive this protection under certain circumstances. (Sections 1932(a), 1115 and 1915(b) of the Social Security Deed.)

Medicaid besides provides special protections for American Indian and Alaska Native beneficiaries who are enrolled in an MCO that is not operated by the IHS, a tribe, or and urban Indian health program. Medicaid MCOs that enroll American Indian and Alaska Native beneficiaries must have a sufficient number of Indian health providers participating in their networks to ensure timely access to intendance for American Indian and Alaska Native enrollees. The MCO must also permit the casher to select an Indian health provider as his or her primary care provider. In addition, the state must permit an American Indian and Alaska Native beneficiary to go outside the managed network to seek care through an Indian health program or urban Indian organization, and there are requirements to ensure the Indian providers receive payment for services provided.(Sections 1932(h)(one) and 1932(h)(2)(A)(i) of the Social Security Human activity; State Medicaid Director Letter, ARRA Protections for Indians in Medicaid and CHIP (SMDL #10-001) (January 22,2010).)

The 100% federal matching rate for services provided to American Indians and Alaska Natives through IHS- and tribally-operated facilities is express to services covered by the state Medicaid program. Although state Medicaid programs are required to cover certain benefits, similar inpatient hospital and physician services, they have flexibility as to whether to cover other "optional" services like dental care for adults. There is significant variability beyond states in coverage of these services, and many states have fabricated reductions in optional services in recent years due to funding constraints. Such reductions in Medicaid services limit admission to services for American Indians and Alaska Natives. Moreover, IHS and tribal facilities do not receive Medicaid reimbursement for providing these services if they are not covered by the state Medicaid program. However, under waiver authority, the Secretary of Health and Human being Services (HHS) has recently approved an approach to enable IHS and tribal facilities to receive uncompensated intendance payments to help get-go costs for services and individuals that are no longer covered past the state Medicaid program (see Appendix A).

States are required to consult with tribes earlier making changes in their Medicaid programs that touch on tribal members. Medicaid is a federal-land program. The formal legal certificate that mediates the relationship between the federal government and a participating state is the State Medicaid Plan, which sets along a land'due south benefits, eligibility, and provider payment policies.31 Although the federal government recognizes tribes every bit sovereign nations, they are not a party to the State Medicaid Plan and practice not have administrative authorization over the Medicaid program at either the federal or state level. The federal regime does, however, require that its agencies consult with tribes. In detail, the HHS, which includes both the IHS and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), has a formal policy that "before any action is taken that volition significantly affect Indian Tribes…to the extent practicable and permitted by constabulary, consultation with Indian Tribes will occur."32 In implementing this directive, CMS requires that state Medicaid programs consult with federally-recognized tribes, Indian health programs, and/or urban Indian health organizations prior to submitting an application for a Section 1115 demonstration waiver33 or developing an integrated care model.34 The federal Medicaid statute also requires that if a Land Medicaid program is amending its Land Medicaid program or seeking a waiver or a sit-in project that "is probable to have a direct result" on Indians, or on facilities operated straight by the IHS facility or past tribes, or on an urban Indian health organization, the State must "solicit advice" from the affected Indian health programs and urban Indian wellness organizations. The advice must exist sought prior to submission of the programme amendment or waiver or demonstration proposal to CMS for review.35

Figure seven: Income of Nonelderly Uninsured American Indians and Alaska Natives, 2009-2011

The ACA Coverage Expansions

Looking ahead, the ACA offers important opportunities to increase coverage and access to intendance for American Indians and Alaska Natives. For all Americans, the ACA seeks to reduce the number of uninsured through an expansion of Medicaid and the creation of new Health Insurance Marketplaces with taxation credits to aid offset the purchase of coverage. Overall, nine in ten (94%) uninsured American Indians and Alaska Natives take incomes in the range to qualify for these coverage expansions (Figure 7 and see Appendix B, Table one for information across states). Moreover, the ACA permanently reauthorizes the Indian Health Care Comeback Act, extending and authorizing new programs and services within the IHS.

The Medicaid Expansion

Under the ACA, Medicaid volition expand to adults with incomes at or below 138% of the FPL ($fifteen,856 for an individual in 2013) in states that implement the Medicaid expansion, which was made a country option by the Supreme Court ruling on the ACA. The federal government will comprehend 100% of the cost for all individuals fabricated newly eligible by the expansion for the first three years, phasing down to xc% over time.36 Regardless of a country's decision to expand Medicaid, the ACA also streamlines the Medicaid enrollment process by providing a single streamlined awarding with multiple avenues for individuals to utilize, reducing paperwork requirements, utilizing engineering to support eligibility determinations, and coordinating with other coverage programs, including new Market place coverage.37

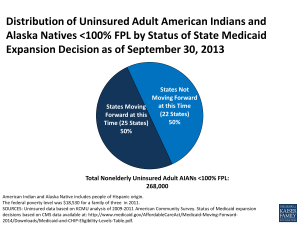

Figure 8: Distribution of Uninsured Adult American Indians and Alaska Natives <100% FPL by Status of State Medicaid Expansion Decision every bit of September 30, 2013

American Indians and Alaska Natives have a pregnant stake in state Medicaid expansion decisions. In states that expand Medicaid, many currently uninsured American Indians and Alaska Natives will gain a new coverage selection as many parents and adults without dependent children become newly eligible for the programme. In contrast, in states that practise not expand Medicaid, poor uninsured adults volition not gain a coverage selection, since those below 100% FPL will non exist eligible for the revenue enhancement credit subsidies for Marketplace coverage. One-half of uninsured adult American Indians and Alaska Natives with incomes below 100% FPL alive in the 26 states not moving forward with the Medicaid expansion at this time (Figure viii and see Appendix B, Tabular array 2 for data across states).38 These adults will not be eligible for Medicaid or the Marketplace subsidies and will likely remain uninsured.

The Medicaid expansion provides the opportunity for increased Medicaid revenues for IHS-and tribally-operated facilities increasing country costs. As noted, Medicaid serves as a key source of revenue for IHS providers, and IHS- and tribally-operated facilities are paid from 100% federal Medicaid matching funds for covered services provided to American Indians and Alaska Natives. This 100% federal matching rate is not tied to the "newly eligible" expansion population and will remain in place when the 100% federal matching rate provided to states for all new eligibles begins to phase down. In states that expand Medicaid, the share of patients served by IHS providers with Medicaid coverage will likely grow, resulting in increased revenues for these facilities that may raise their chapters to provide services. In dissimilarity, in states that do not expand, IHS providers will non benefit from these increased revenues.

Wellness Insurance Marketplaces

The ACA creates new Wellness Insurance Marketplaces in all states that opened for enrollment on Oct 1, 2013, with coverage beginning on Jan 1, 2014. These Marketplaces offer a choice of qualified health plans (QHPs) for consumers to compare and select among at dissimilar price and benefit levels. In addition, tax credit subsidies are bachelor to help offset costs for moderate-income individuals who do not have admission to affordable coverage from their employer.

One in three (33%) uninsured American Indians and Alaska Natives has income in the range to qualify for the revenue enhancement credit subsidies to buy a QHP through the new Marketplaces. As such, the Marketplaces and subsidies will provide new affordable coverage options for many American Indians and Alaska Natives. In improver, a Market may allow tribes, tribal organizations, and urban Indian organizations to pay premiums on behalf of American Indians and Alaska Natives. In that location also are two special protections provided for members of federally-recognized tribes who enroll in a QHP through the new Marketplaces that reflect the federal regime's special trust responsibility to American Indians and Alaska Natives. Specifically, members of federally-recognized tribes take the selection to alter health plans on a monthly, rather than annual, basis and are exempt from cost sharing requirements, such as copayments, coinsurance, and deductibles, if their income is below 300% FPL or they receive directly services or a referral from an IHS provider.39 Nevertheless, these protections do not utilize to the broader group of American Indians and Alaska Natives who are eligible for IHS services and afforded special Medicaid protections.

Private Requirement to Have Health Insurance

Along with the coverage expansions, the ACA besides establishes a new requirement for most individuals to accept health insurance. Specifically, most individuals are required either to have "minimum essential coverage" or to pay a tax penalty. In general, individuals who accept coverage through their employer or purchased on the individual market; are covered by public insurance programs like Medicare, Medicaid, or the Children's Health Insurance Program (Flake); or who have certain types of coverage through the veteran's health program volition be considered to have met this requirement.twoscore In contrast, individuals relying solely on intendance provided by HIS, without other health coverage, will not be considered to have minimum essential coverage. Under the ACA statute, American Indians and Alaska Natives who are members of federally-recognized tribes are exempt from the requirement to have minimum essential coverage. Recent regulations as well added a hardship exemption from the requirement for all individuals eligible for IHS services, which is consequent with the broader group of American Indians and Alaska Natives afforded special Medicaid protections and provisions.41

Looking Alee

Looking ahead there is an array of challenges and opportunities to improve access to care for American Indians and Alaska Natives and aid reduce the longstanding health disparities they face:

Admission to IHS services will probable become even more limited as a result of automatic federal upkeep cutbacks under the sequester. IHS is a discretionary programme with funding based on annual appropriations by Congress. As a discretionary program, the IHS is subject to the automatic, beyond-the-board federal upkeep cuts that were triggered every bit of March i, 2013 nether the sequester. Overall, the Part of Management and Budget estimates that the IHS will exist subject to 5% upkeep cuts under sequestration. The Part of Management and Budget estimates that the sequester volition issue in a $220 million budget cut for IHS during the 2013 federal financial yr which, according to IHS, will lead to three,000 fewer inpatient and 804,000 fewer outpatient visits each year.42 These upkeep cuts directly touch the availability of resources for tribal and urban Indian operated facilities too. These restrictions volition further limit the power of American Indians and Alaska Natives to access services through the IHS, tribal, and urban Indian providers and, as such, increment the importance of the ACA coverage expansions for the population.

The Medicaid expansion provides a meaning opportunity to increase coverage and intendance for American Indians and Alaska Natives. In states that expand Medicaid, many parents and childless adults volition become newly eligible for the program, providing a new coverage option for many currently uninsured American Indians and Alaska Natives. Widespread evidence suggests that obtaining health insurance coverage leads to improved admission to care and wellness care utilization. Individuals who are insured are more probable to become recommended levels of preventive intendance, higher quality intendance, and to have better health outcomes. Moreover, for American Indians and Alaska Natives who currently solely rely on IHS services for care, gaining Medicaid coverage may increase access to providers, since they will no longer be limited to care at IHS- or tribally-operated facilities. At the same time, increases in Medicaid coverage may also assistance expand capacity within IHS- and tribally-operated facilities since their Medicaid revenues will increase if more than patients enroll in Medicaid. Overall, the importance of Medicaid every bit a source of financing for health care for American Indians and Alaska Natives is likely to abound over the next decade as federal upkeep pressures constrain IHS appropriations at the same time as the Medicaid expansions in the ACA are implemented.

American Indians and Alaska Natives volition continue to face pregnant gaps in coverage and face growing inequities in coverage and care in states that exercise not aggrandize Medicaid. While the Medicaid expansion offers the opportunity to significantly increase coverage amid American Indians and Alaska Natives, as of September 30, 2013, 26 states were non moving forwards with the Medicaid expansion at this fourth dimension. In states that do not expand Medicaid, poor uninsured adults volition not gain a coverage pick and likely remain uninsured. Similarly, IHS providers in states moving forward with the expansion will likely experience greater revenue gains than those in states non moving forward. Moreover, state Medicaid expansion decisions volition create unique equity bug for American Indians and Alaska Natives since there are tribal nations with boundaries that extend across states that accept made differing expansion decisions. For instance, the Navajo nation extends into Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico. Arizona and New Mexico are moving forward with the expansion, while Utah is non moving forward at this time. Equally a event, a Navajo tribal member living in Arizona may have admission to Medicaid coverage, while a Navajo member (meeting the same income and eligibility requirements) living in the Utah might not. Equally such, state Medicaid expansion decisions will bulldoze variations in coverage, admission, and health status both within and between tribes.

The new Marketplaces also will provide a new coverage option for many American Indians and Alaska Natives, but simply members of federally-recognized tribes will receive certain consumer protections. As noted, the new Marketplaces volition provide additional protections to members of federally-recognized tribes, including the ability to change health plans on a monthly basis and some exemptions from price-sharing. Still, these Market protections practice not utilise to the broader grouping of American Indians and Alaska Natives who are eligible for IHS services, afforded special Medicaid protections, and exempt from the individual requirement to have wellness insurance. This inconsistency will result in many American Indians and Alaska Natives non receiving these protections. It also will probable contribute to defoliation and uncertainty, particularly since the Market and Medicaid application processes volition be integrated, which may hamper outreach and enrollment efforts for American Indians and Alaska Natives.

Targeted outreach and enrollment efforts and access to culturally competent providers volition be key for translating the coverage expansions into improved care for American Indians and Alaska Natives. Past Medicaid and CHIP experience suggests that targeted outreach and straight 1-on-one enrollment assistance provided by trusted individuals within the community volition be important to help eligible people enroll in the ACA coverage expansions. Involving tribes, tribal organizations, and urban Indian organizations in outreach and enrollment efforts will be vital for enrolling uninsured American Indians and Alaska Natives in coverage and ensuring they have access to linguistically and culturally appropriate enrollment assistance. The ACA establishes a diversity of consumer assistance programs to support enrollment and allows for tribes and tribal organizations to provide help, simply outreach and enrollment assist efforts will probable vary widely across states. Beyond supporting enrollment in coverage, it will also be important to connect individuals to providers who can provide linguistically and culturally appropriate care. States are required to piece of work with tribes to ensure that Indian providers are included in provider networks nether Medicaid. Market place QHPs must meet standards related to including "Essential Community Providers" in their provider networks, which include Indian providers. However, concerns remain about network adequacy and travel times to participating providers, particularly for individuals living in remote areas. In conclusion, while the federal government has a distinct responsibility to provide health care to American Indians and Alaska Natives, many face challenges accessing needed care and the population continues to experience poor health outcomes, including high rates of chronic disease. The IHS is the principal vehicle through which the federal authorities provides health care to American Indians and Alaska Natives. However, due to its limited funding, the IHS is not able to fully meet the need for care. Moreover, as individuals increasingly motility away from reservations, many cannot admission IHS facilities. American Indians and Alaska Natives also have express admission to private health coverage given their low incomes and employment patterns. While Medicaid helps fill this gap, many uninsured adults remain ineligible for the program and some eligible individuals remain uninsured due to enrollment barriers. Looking alee, American Indians and Alaska Natives keep to face many challenges to accessing care, including further decreases in IHS funding. Nonetheless, the ACA coverage expansions provide important opportunities to increment their coverage and access to intendance, which could help reduce the longstanding health disparities they face.

This cursory was prepared past Samantha Artiga and Rachel Arguello with the Kaiser Family Foundation'southward Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured (KCMU) and Philethea Duckett, formerly with KCMU. The authors thank Andy Schneider, former consultant to KCMU; Kitty Marx, with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Geoffrey Roth with the Indian Health Service, Ralph Foquera with the Seattle Indian Wellness Board, and Doneg McDonough for their helpful review and comments.

mcneilhartatied1956.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.kff.org/report-section/health-coverage-and-care-for-american-indians-and-alaska-natives-issue-brief/

0 Response to "Individual Vs Family Focus in Native American Healthcare"

Post a Comment